“It’s All About the Nectar, Honey!”—A Sneak Peek into the Sweet and Sour Life of a Trumpet Creeper (Campsis radicans)

Fig 1: The bright red flowers of the trumpet creeper (Campsis radicans). (Photo credit: iStock)

For a moment, teleport yourself to a place somewhere in the wilderness of North America. Make-believe that you are a beautiful orange flower hanging from the woody vine of a trumpet creeper (Campsis radicans). You are one of the many flowers that adorn this prolific bloomer, a hardy plant which is invasive enough to take over any backyard. Your prolific nectar-producing factories are legendary, and you seem to have a sweet treat for everyone who comes calling. No wonder, a host of customers (and others) regularly line up to have a taste of your riches. The list includes the who’s who of the pollination world—bees, ants, birds and whatnots. And why not? Wasn’t that the whole purpose of the prolific nectar production—to entice the pollinators to perform the crucial task of transferring your pollen to a receptive stigma? As Sue Hubbell, the author and beekeeper, memorably put it, “My bees cover 1,000 square miles I do not own in their foraging flights, going from flower to flower for which I pay no rent, stealing nectar but pollinating the plants in return.”

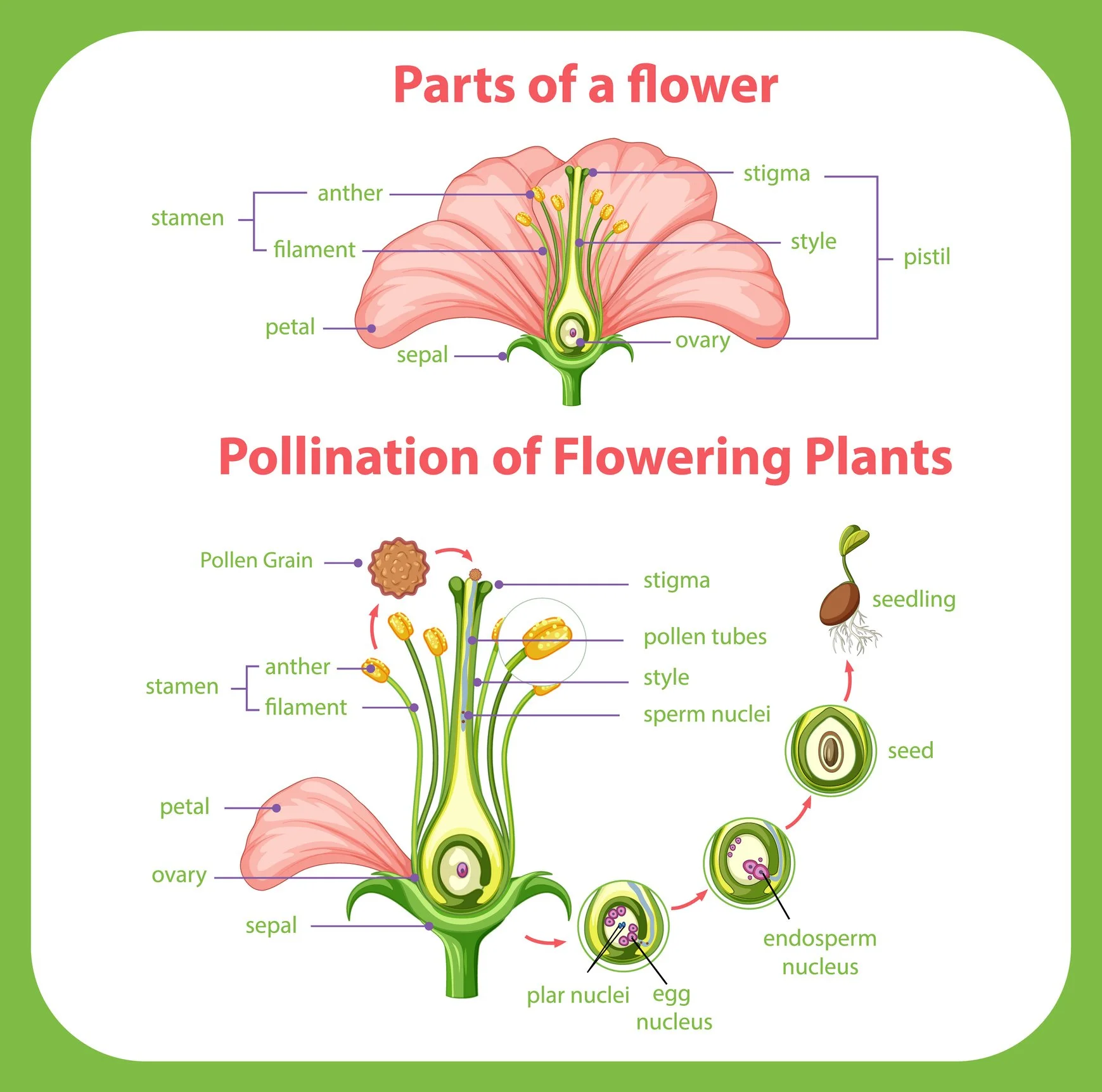

(For those of us who have forgotten our middle school pollination lessons, the figure below will provide a good recap)

Fig 2: Internal Structure of a Flower and the Process of Pollination in Flowering Plants. (Photo credit: iStock)

There’s a catch though. Not all pollinators are fit for the task that you expect them to do. And the nectar in your kitty is not a free-for-all sweet treat! Nectar-making is serious business, one which significantly escalates your energy bill. Nonetheless, you still churn out your nectar potions owing to their usefulness as a trading currency. Given how valuable this currency is, it is only fair that it is highly guarded with restricted access to unscrupulous visitors.

But how exactly do you do that? How do you entice your favored pollinators with your nectar, while also safeguarding it from pickpockets and full-fledged robbers?

This is the point where we pause our discussion and applaud your ingenuity at establishing a stable, long-standing relationship with the ruby-throated hummingbirds (Archilochus colubris) [1]! Once upon a time, some curious hummingbirds chanced upon the copious amounts of energy-dense nectar in your safe. Having stumbled upon the treasure chest, the hummers quickly became dependent on you as their most important source of nectar. So dependent, in fact, that observers have predicted a profoundly negative impact on hummingbird populations if your kind, that is, the trumpet creepers, were to disappear altogether [2]. The vice versa may not be true, though, for you have other pollinators (like bees) on the roll call. Your partnership with ruby-throated hummingbirds is definitely your most fruitful one (literally!), but it is not the only one. The fact remains, though, that hummingbirds can deposit 10 times more pollen per visit when compared to bumblebees and honeybees [1]. This is perhaps the reason why you adore the hummingbirds just as much as they love you. If there is one group which knows exactly what you want, it is the hummers!

Fig 3: BFFs- Trumpet creeper (Campsis radicans) and ruby-throated hummingbirds (Archilochus colubris). (Photo credit: iStock)

There is another group of birds which knows exactly what it wants; your needs be damned! Please shine the spotlight on orchard oriole (Icterus spurius), the nectar-robbers! They want your goodies, but won’t pay for them. Of course, you had accounted for this possibility and come up with two design modifications to deter any would-be robbers:

(a) thickened calyces (a whorl of sepals is called a calyx), which would prevent easy access to the nectar

(b) fused petal bases, which are meant to remove gaps which may be exploited by shoplifters

Unfortunately, these measures seem to have done little to deter the orchard orioles! Armed with sharp beaks, they ruthlessly puncture your petal bases and extract the nectar, totally bypassing the pollination step and leaving you with punctured petals and an unpollinated flower—a textbook example of a one-sided relationship. Unfortunately, the lopsided love seems to be highly prevalent; a researcher estimated that 92% of your next of kin were robbed in this manner by the orioles [3]. In fact, your relationship with the orioles has even been suggested as a model system to study nectar-robbery!

Fig 4: The nectar-robber: Orchard oriole (Icterus spurius). (Photo credit: iStock)

The passage above will make some think that the hummingbirds and the orioles fit perfectly into the respectable-customer-vs-robber narrative. Time to make things a bit more interesting! Although hummingbirds come across as paying customers, they are not averse to a little shoplifting, conditions permitting. If you observe some hummers hovering over you before approaching, it is because they are surveying for flowers pierced by the orioles; an enticing shortcut to delicious nectar [1]! How unethical—you might think. If the birds are capable of paying for nectar through pollination, the way they always have, why would they suddenly refuse to pay and turn to shoplifting?

Although not much is known about this part of the decision-making by hummingbirds, let us give them the benefit of doubt—they are probably doing it for safety reasons. And that trumpet shape of yours might be responsible to some extent! Alright, we do accept the importance of the shape in achieving the desired outcome for you. Having a trumpet shape ensures that the hummingbird’s head is coated with pollen when it dives deep in to extract nectar. On the bird’s subsequent expeditions to other flowers, the pollen on its head with rub onto a receptive stigma, thereby capping a successful pollination cycle. How intelligent! It is a prickly situation for the birds, though. Every time a hummingbird dives deep into the ‘trumpet’ for nectar, its view of the surroundings is obstructed, thereby making it vulnerable to predators. Stealing nectar from flowers already pierced by the orioles might simply be an attempt at mitigating that risk.

In view of the complicated relationships with hummingbirds and orioles (is the latter even a relationship?), who would ever say no to the option of pollination by bees [4]! The conspicuous ‘nectar guides’, visible as reddish lines extending from the mouth of the ‘trumpet’ to the nectar pools, are a signal to the bees that they are always welcome. The nectar guides are lane markers that let an assortment of bees know where the nectar pots are. When the bees take the cue and start moving towards the nectar pool, it is a given that they will also pollinate in return. A win-win situation!

Fig 5: A bee inside the flower of a trumpet creeper. Note the reddish lines in the background-these are the lane markings (aka nectar guides) showing the way to the nectar pools inside the flower. (Photo credit: iStock)

Now that we understand your strategy of enticing multiple pollinating customers with copious amounts of nectar, it is remarkable that you also prepare nectar potions outside flowers for visitors who have nothing to do with pollination. Time to welcome the ants into this story! The hummingbirds are indulged with a specific purpose in mind; the same holds true for the ants too! Before unravelling the mystery, let’s have a sneak peek at your different nectar factories.

In modern parlance, your fine dining restaurant, situated at the deep end of the ‘trumpet’ and filled with copious amounts of nectar, is reserved for the most coveted group—the pollinators. Here, the hummingbirds and the bees are given a red-carpet welcome—after careful vetting, of course. They enjoy a hearty meal of your nectar and pollinate in return. There are ‘No Entry’ signs put up to deter nectar robbers like Orchard orioles, manifested in the form of thickened calyx and fused petal bases. They rob, nevertheless, and lay waste to your beloved kitchen.

The surprise package of your gourmet business are your kitchenettes, though—the underappreciated extrafloral nectaries found on the calyx and the pedicel (the flower stalk). Roughly equivalent to food trucks, they specialize in doling out sugary extrafloral nectar, thereby attracting a plethora of insects, including ants. If pollination has already been ruled out, what other purpose can these insects possibly serve? SECURITY! Turns out that the extrafloral nectar primarily attracts insects of the order Hymenoptera (which includes ants). Even within this order, it is the insects of the Chalcidoidea superfamily which show an overwhelming response to the offer of free extrafloral nectar [5]. The Chalcidoideans have a fearsome reputation; they are the thugs of the insect world. This insect superfamily is composed of parasitoid wasps which feed on other insects in their larval stage. The ‘other insects’ that the Chalcidoideans munch on happen to be much-hated plant pests, including aphids and some beetles. Hence, scientifically speaking, the Chalcidoideans act as biological pest control agents; plain-speaking, they act as bouncers who gobble up unwanted pests attempting to break into the plant’s defenses. The thugs also scare away any pollinators who may be tempted to take a shortcut to the main nectar pools by biting open the flower base. Interestingly, the extrafloral nectar does not attract the primary pollinators. They are too spoilt by the rich taste of the main nectar made for them by you, their BFF. The plain extrafloral nectar is reserved for the stinging insects who became your friends solely by virtue of the common adage, “The enemy of my enemy is my friend!”

Fig 6: An ant on the calyx of a trumpet creeper flower. (Photo credit: iStock)

References:

[1] Graves GR (2024). Ornithophily in the trumpet creeper (Campsis radicans). Ecology and Evolution. 14:e70279. doi: 10.1002/ece3.70279. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ece3.70279

[2] https://www.rubythroat.org/RTHUEcologyMain.html

[3] Graves GR (2022). The Campsis-Icterus association as a model system for avian nectar-robbery studies. Scientific Reports. 12:11936. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-16237-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9279294/

[4] Van Nest BN et al. (2020). Bees provide pollination service to Campsis radicans (Bignoniaceae), a primarily ornithophilous trumpet flowering vine. Ecological Entomology. 46(1):117-127. doi:10.1111/een.12947. https://resjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/een.12947

[5] Mihajlovic L (2018). Chalcidoidea Species (Insecta:Hymenoptera) on the Woody Vine Campsis radicans (L.) Seem. Ex Bureau. Acta Entomologica Serbica. 23(1):51-77. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1477931.